-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Discussions

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

- Macmillan Community

- :

- English Community

- :

- Bits Blog

- :

- Manga on Manga: Thinking about Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s...

Manga on Manga: Thinking about Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life in the Comp Class

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

[This post was originally published on October 30, 2012.]

component seeps its way into my pedagogical fantasies, and this week is no different as my current

fantasy takes its inspiration from Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s amazing pseudo-memoir A Drifting Life.

Jonathan

In an earlier blog, I wrote about Tatsumi’s development of gekiga, a grittier, more adult version of manga. Collections of his work translated into English in the last several years include the remarkable Push Man and Other Stories, which bring together several of Tatsumi’s “shorts”—startling and provocative slices of post-war Tokyo life, full of economic desperation, difficult family situations, lovelorn lives, and erotic dysfunction. Tatsumi inspired other manga artists, including the grandfather of manga, Osamu Tezuka, to explore more adult themes and content in their work and helped establish manga as a medium not just for kids, but as a venue through which more “graphic” subjects might be rendered and considered.

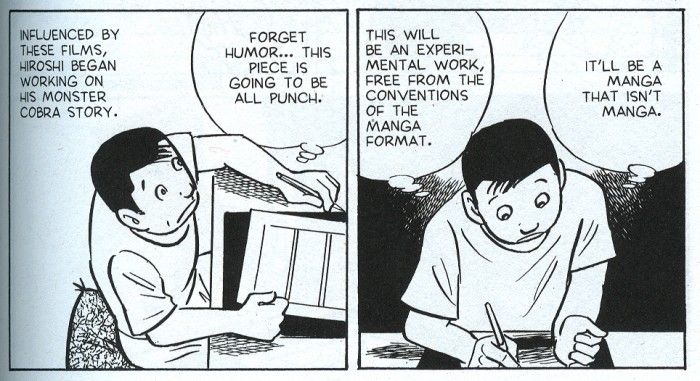

Originally published in Japan in 2008 and released in the US by Drawn and Quarterly in 2009, A Drifting Life is a large volume “memoir,” depicting in somewhat fictionalized form Tatsumi’s coming of age in post-war Japan and his early love of manga, which he steadily turns into an artistic career. The book lovingly details the different kinds of manga that Tatsumi read as a youngster, as well as his initial attempts to imitate the artists he loved. We see him struggling with mastering elements of plot (for adventure-oriented manga) and then steadily developing his own particular style and thematic concerns. Tatsumi excels at exploring how his narrator (ostensibly based on himself) must deal with the pressures to conform to publishing demands, which often required that manga artists produce page and page of original material on a weekly basis. Still, Tatsumi has his own vision, and negotiating that vision with fan expectations as well as the economic realities of publishing in post-war Japan is at the heart of this memoir.

Many compositionists have their students write literacy narratives. Ultimately, A Drifting Life is a sustained, critical, and often provocative literacy narrative about becoming a manga artist. Central to its narrative concerns are a mapping out of the narrator’s coming into awareness of the different genres of manga available in post-war Japan, but also, just as key, an awareness of the economics of literacy. Many Japanese after the war were too poor to buy manga, so lending libraries emerged to help folks get access to the popular emerging medium. Moreover, the desire for escape and fantasy from economic hardship fueled much of the genre’s early content. These forces and influences are as much a part of Tatsumi’s literacy narrative as are his boyish love of well-drawn adventure stories.

As a compositionist, I also appreciate A Drifting Life for its emphasis on working with audience concerns and expectations while also honoring the particularity of authorial voice and vision. That Tatsumi can explore some wonderful material in a manga about making manga adds to some of the thrill of the text; we see Tatsumi’s style develop literally before our eyes, in panel after panel Tatsumi shows us his inspirations and his foils, the work that inspires him and the work against which he struggles to articulate and render his own vision of what manga can be. A Drifting Life offers a powerful meta-narrative about the arts of composing, and I can see it as a central text in a first-year or advanced composition course devoted to multi-modal writing.

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.