-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Discussions

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

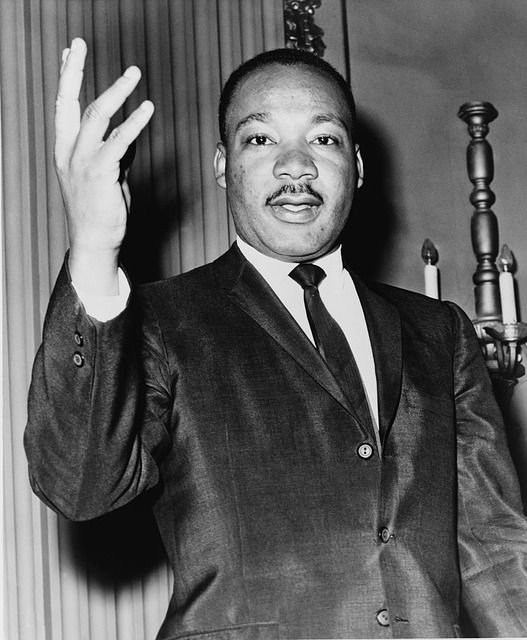

Thinking of Martin Luther King Jr.

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

I’m writing this posting on January 21, MLK day, and so I have been thinking of him and of his legacy as I do every year this time. Of course I remember exactly where I was on Thursday, April 4, 1968: I was still at the school where I was teaching 10th and 11th grades, working on plans and reading student work when a colleague knocked and told me King had been shot. I rushed home and, like most of the rest of the country, turned on radio and TV and sat, horrified and weeping, at what I was seeing and hearing. I remember feeling as if our country was close to exploding—so much hatred and violence. And of course I didn’t even know at the time what was coming—more assassinations, more protest, more violence, more hatred.

But King’s legacy has been about love and peace and connecting, not with violence and hatred, and that is one reason for hope, even today when, once again, hatred and racism and violence are on the rise. King’s message rises above all that and offers hope. We need that message now more than ever.

On this day, I am gathering donations for our local food bank, and I expect many of you are offering some service today as well. In addition, I want to recommend two items for teachers of writing everywhere to consider as we think of MLK. The first is a brief video produced by the Annenberg Foundation Trust in partnership with the Gandhi King Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice in honor of Dr. King's 90th birthday. As you’ll see, the video features interviews with civil rights leaders conducted by documentary filmmaker Jesse Dylan. I loved hearing these inspiring voices and the message they bring to us today.

Secondly, I am currently reading The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea by Christopher J. Lebron. It’s not an easy read for me, each chapter leaving me seething with anger at the injustices so thoroughly documented while also admiring Lebron’s scholarly work and especially his use of some of my own personal heroes—Ida B. Wells, Audre Lorde, Zora Neale Hurston, Anna Julia Cooper. In it, Lebron traces not just the history of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag but the ideas and feelings and struggles of a much older, rich tradition preparing for this imperative demand for equal rights—and equal dignity.

White people like me need to ask ourselves if we are among those Lebron refers to as “morally dimwitted,” that is, people who are convinced of the rightness of their own positions yet “whose moral perceptions are so deeply mired in racial privilege that the critical perception and judgment needed to correctly interpret problems is suppressed to the point of motivating asinine observations and assertions.” As an example of such moral dimwittedness, Lebron asks readers to “imagine what it is like to read, as a black person in the wake of Freddie Gray nearly losing his head—literally—while in police custody: well, if he wasn’t doing anything wrong, why did he run? As if being legitimately afraid of the police . . . were reason at all to be practically decapitated by the state.” Have you heard such questions asked after a police killing of a young black male? I certainly have and I expect our students have too. Lebron asks us to face such dim-wittedness head-on, revealing it for what it is and offering a different, and more just, question in its place.

Lebron’s searing history is dark and devastating. But he does see some reason for hope when “three women decided that not one more black person’s life would be taken without America being forced to answer the question that black intellectuals have been asking for more than one-and-a-half centuries: do black lives in America matter or not.” Lebron concludes that we are still waiting for the answer to this question.

Writing programs and writing teachers can continue to ask the question, and can engage their students in looking at various answers to it and examining their own responses. We can ask students to analyze their own assumptions and those nearest to them, to learn to look at issues from other perspectives and to listen to those who hold those other perspectives openly and with respect. There is good work that we can do to help answer the question “do black lives matter” and, in doing so, to honor the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.

Image Credit: Pixabay Image 393870 by skeeze, used under the Pixabay License

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.