-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Discussions

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

- Macmillan Community

- :

- English Community

- :

- Bits Blog

- :

- Visual Literacy for a Pandemic: Beyond Flattening ...

Visual Literacy for a Pandemic: Beyond Flattening the Curve

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

Striving for community in this strange and estranging moment, I am here to champion the work we do—even in non-global-pandemic times—to teach our students the value of critical visual literacy. Now, these lessons are even more crucial.

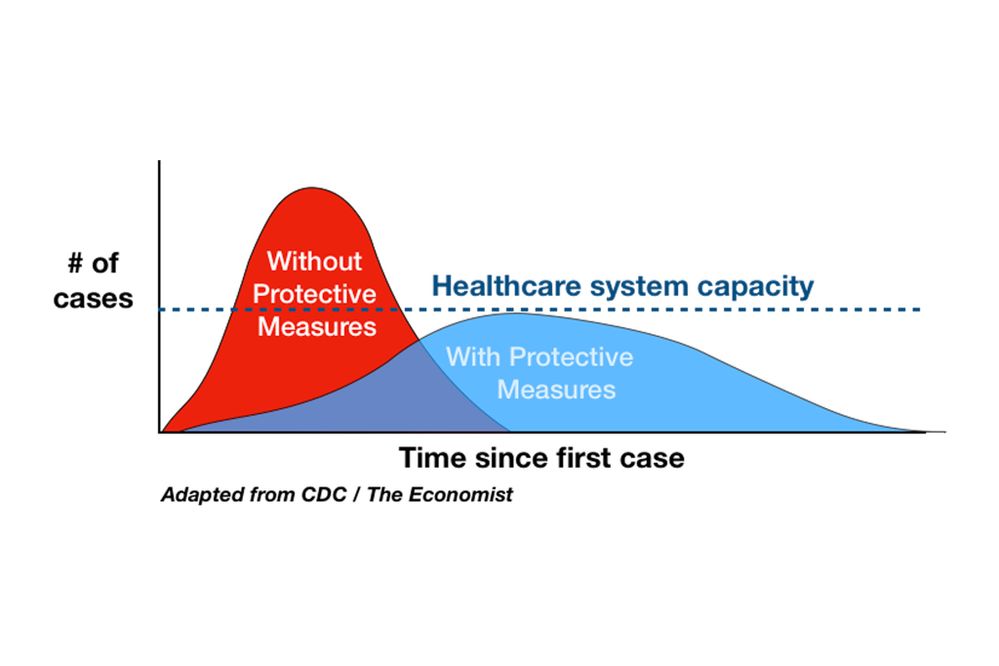

Isn’t it fascinating how this particular image of coronavirus-related health behaviors took off a few weeks ago?

The simplicity of the visual rhetoric made this a highly shared and hashtagged image (#lowerthecurve) since it clarified the math of exponential infections. Fast on its heels, though, came critiques about the shortcomings of its simplicity. Then came a tsunami of more nuanced public health visuals, any of which could make for interesting teaching, including this free-to-access Washington Post series of models.

By the time you are reading this and are navigating the process of teaching the rest of your semester online, you already might have designed assignments that address this unsettling, united-in-our-social isolation moment, perhaps by inviting students to analyze, compare, and critique these pandemic-related images. For assignment inspiration, you might revisit Bedford New Scholar Carrie Wilson’s post on visual rhetoric and digital literacy.

Because March is also Women’s History Month, I’d like to recognize that while we are rightly celebrating the scientists who are working hard to address the pandemic, we might also acknowledge the barriers to careers in science that remain widespread for women.

I give a shout out to two women who contributed early on to the science of public health in this essay for our local NPR affiliate, WVPE. There are many more women scientists to celebrate, but they are still a minority in most scientific fields.

In the forthcoming 5th edition of From Inquiry to Academic Writing, co-authored with Stuart Greene, we offer a pithy reading on “Global Gender Disparities in Science” that includes visual representation of the gender imbalance in scientific research output.

In this very teachable text, Cassidy R. Sugimoto and colleagues use bibliometric analysis to demonstrate the structural inequalities that keep women from pursuing and succeeding in many scientific fields:

Our study lends solid quantitative support to what is intuitively known: barriers to women in science remain widespread worldwide, despite more than a decade of policies aimed at leveling the playing field. UNESCO data show that in 17% of countries an equal number of men and women are scientists. Yet we found a grimmer picture: fewer than 6% of countries represented in the Web of Science come close to achieving gender parity in terms of papers published. (From Inquiry to Academic Writing, 5e)

Sugimoto et al. argue that we are cheating ourselves out of crucial scientific insights when a country fails to “maximize its human intellectual capital.”

This pandemic is already teaching us many things. Reminding us of the value of science, and public understandings of scientific research, is among those vital lessons.

Photo Credit: Pixabay Image 3412498 by kreatikar, used under Pixabay License

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.