-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Discussions

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

- Macmillan Community

- :

- English Community

- :

- Bits Blog

- :

- Collaborative Documents and Student Centered Class...

Collaborative Documents and Student Centered Classrooms

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

This post first appeared on December 2, 2014.

I’ve been a slow adopter of using Google Drive, despite many years of having Google-supported email at the different universities where I’ve worked.

But in my late adoption of it, I’ve come to realize how useful it can be in the classroom, particularly when it comes to facilitating a lot of the work that I do to create a student-centered discussion.

I realized over the summer that I could use Google Drive for a couple of things. The first was to create journal templates for my students in my 100- and 200-level courses. In those courses, my students keep daily reading journals — and by having students write in a journal that I can see, I can immediately tell who is doing the work. More importantly, I can draw ideas into the classroom that students write about in their journals. It took some work to set everything up (I created a template, then made copies for all of the students), but it’s been a useful way to keep an eye on what interests the students in what they read.

My other major use of Google Drive is to create what are essentially collaborative documents of discussion questions. I did this initially because I’ve got an assignment that’s always been a bit clunky for me in terms of organization. In my 300- and 400-level courses, I’ve always taught students how to write open-ended discussion questions, and then I’ve had them submit questions daily (in lieu of a quiz). We use those questions in class to guide our conversation.

Previously, I’ve tried having the students just hand the questions to me in class (which really made me work on the fly) or email me either the night before or the hour before class. With the email, I wound up spend a lot of time collating the work, which also meant the potential for missing some of the questions in the overflowing email inbox. As I was preparing for my courses over the summer, I remembered an admonition from my student teaching days — if you can let the students do the work for you, have them do the work for you. Thus, for this, I’ve got the students in my upper division courses writing and collating their discussion questions in Google docs. Here, I simply created forms for each day of class — titled with the name of the text we’re reading and the assigned chapters of acts — and shared an entire folder with the class. Students submit questions until 30 minutes before class — then I print the entire thing off and use it as we work through the literature. I’ve found that students’ questions are less repetitive when they see what’s been asked before — and I’m even noticing that students will sometimes reference other students’ questions in their own (in which case, I know we have to discuss a certain topic).

I went into the semester thinking that this would be all we use shared documents for.

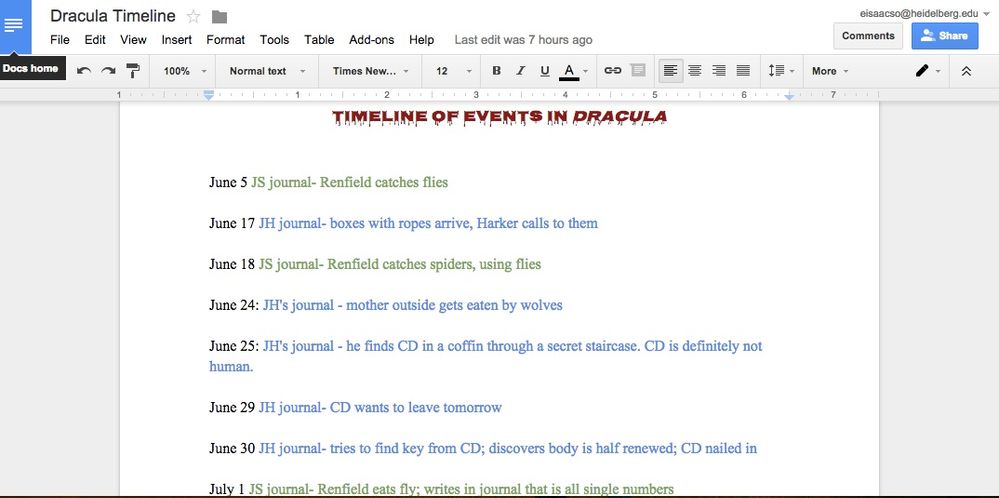

Then I decided that the students in my novels course really needed to take a careful look at the chronology of events in Dracula. I realized that this was not something we could really just do on the blackboard. We’ve been doing chapter-by-chapter breakdowns of plots at the beginning of class, but there are simply too many days and too many different narrators in Dracula for that to be effective.

So I created a shared document that simply lists all of the dates in Dracula when a character writes in a diary, sends a letter, or receives a message from a solicitor’s office. On the first day of class, I shared it with all of the students in the class, projected it from the overhead, and set students to the task of sorting things out. Students worked in groups of two or three, huddled (admittedly) around their phones, laptops, tablets, and the classroom computer, adding to the chronology together.

Once we spend the first chunk of class doing that, we take a look at the story in order — and it’s really helped the students find the details of Dracula’s movements (“Oh, wait! That’s what the dog on the ship was!” “Oh, that’s why there was the detail about the escaped wolf!”). I also color code the document, according to the different characters narrating (i.e. John Seward’s diary is in green, Mina Murray/Harker’s journal is in purple), which allows us to see how the narrative bounces from one character to another, and how the characters themselves have to piece information together over time.

In doing this we’ve been able to have an effective discussion of the structure of the novel, which has shown the students that they can, indeed, break down the narrative into its parts and look inside the inner workings of the novel.

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.