-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Discussions

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

- Macmillan Community

- :

- English Community

- :

- Bits Blog

- :

- What’s the Motivation?: Teaching Characterization ...

What’s the Motivation?: Teaching Characterization in Drama

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

This week's featured guest blogger is Joseph Couch, Professor at Montgomery College.

“But why do that?” students often ask when we discuss plays. Sometimes due to the opaqueness of subtext or even with the seeming (at least to experienced readers) transparency of dialogue and action, characters’ motives can puzzle readers. Without a narrator to provide the thoughts and feelings of at least one if not all characters, drama requires recognizing some different textual clues from fiction. Characterization in both genres, though, in works from the modern period to the contemporary, as well as quite a few before it, relies on a psychological approach based on motivations. Getting students to recognize what drives characters, who in the early stages of reading a play may seem like random blocks of dialogue on the page with little to differentiate them, can be quite challenging. Another challenge for instructors is to prevent a literature class from becoming Psychology or Method Acting 101 in the process of teaching characterization in drama.

To help students better understand characterization in drama, I developed a small-group classroom activity that instructors can use at any point in the discussion of a play or as part of a review for a paper or exam. The starting point is for the class to identify an important moment or moments in the text that have serious rewards or drawbacks for a character or characters. This added warm-up can help students from only looking for dialogue and directions related to the one character in question. After assigning a moment and character(s) to the groups, the activity proceeds as follows:

1. Students list the reasons/motivations why a character makes the decision and/or takes the action with support from dialogue and direction in the play, usually two or three reasons will suffice.

2. Students also consider and list the character’s goals for the decision and/or event. The instructor may need to remind students that these goals may be quite different from the actual outcomes for the characters.

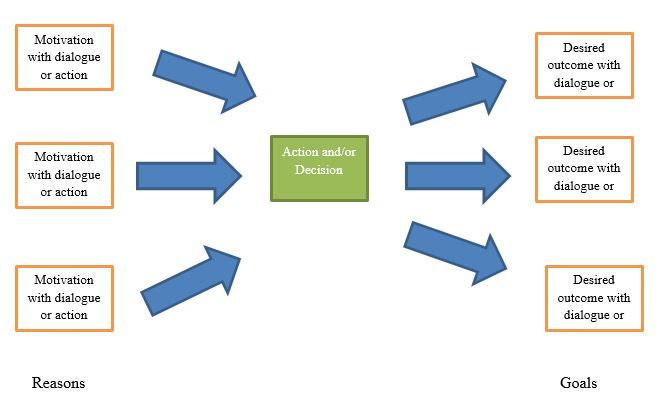

3. A simple flow chart presented on the board can help students follow the logic of the character’s motivations and goals. Distributing hard copies of the chart to the groups to use can also help keep them on task. On one side are the motivations that lead to the action and/or decision in the middle of the chart. On the right side are the character’s desired outcomes. A sample chart is below:

4. Once groups have completed the charts/provided answers, each group does a mini-presentation for the class of motivations and goals. To frame the discussion of characterization within the larger context of the play and other dramatic elements, some questions to ask of the class as a whole can be:

- How practical are the motivations and/or goals of the character, and what clues does the text provide?

- Does the character achieve the goal—why or why not?

- How does the setting contribute to and conflict with the character?

- Which characters have competing motivations and goals, and how do they complicate the plot?

Each small group can work with the same character and event or with different ones, depending on the number of characters and complexity of the plot as well as how challenging the students find characterization in this text. It can also be helpful to review with students that what other characters say and do towards or in response to a character are also part of characterization. This discussion during the warm-up can help the small groups and whole class to avoid just looking for and discussing the assigned character as if he or she were along on the page and stage. Classes can also revisit this activity during work on an individual play for clarification and/or use these steps for multiple plays in a unit or course. The ultimate goal is for students to start asking “But why do that?” as they read, discuss, and write about plays as part of their regular engagement with them. With practice, students can answer that question for themselves, both within the plays they read and within their own reading processes.

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.